Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII), the largest military shipbuilder in the United States, occupies a critical role in national defense infrastructure. With exclusive contracts for nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and a dominant position in submarine production, HII’s investment thesis revolves around its structural advantages, growing demand for naval assets, and potential margin recovery amid evolving defense priorities. The key pillars are long-term defense budget tailwinds and operational improvements.

The Company

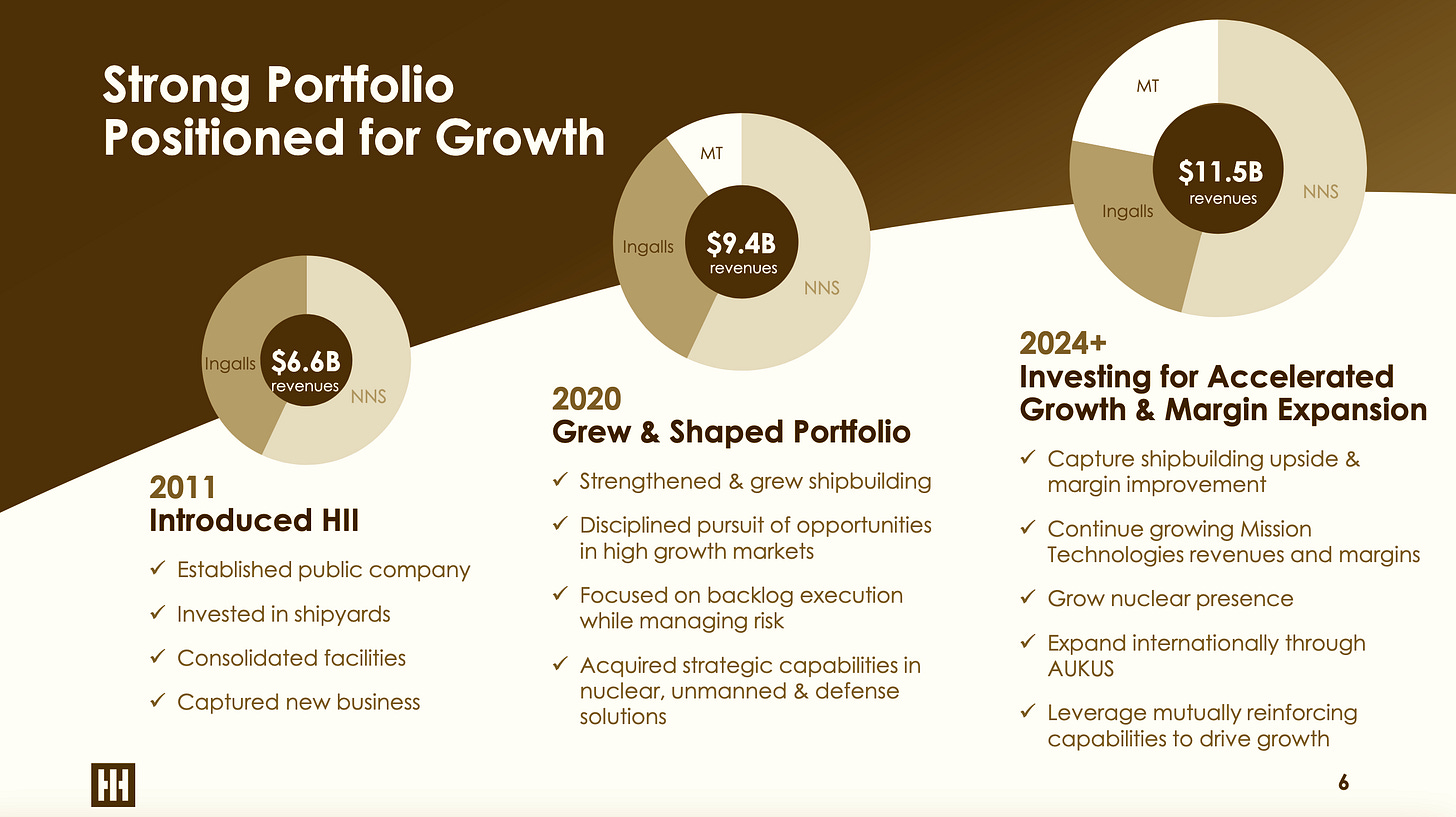

HII started its life as an independent company in 2011 as a spin-off from Northrop Grumman. The following slide from its March 2024 investor presentation sums up its development since.

As you can see, HII operates through three segments, roughly split 50-25-25.

Newport News Shipbuilding - Sole provider of U.S. Navy aircraft carriers and one of two nuclear submarine shipbuilders with 140 years of history. This segment has remained more or less a constant part of the business, which roughly doubled in size since the spin-off. However, it faced a 4% revenue decline in the last quarter due to labor shortages and cost overruns in Virginia-class submarine production.

Ingalls Shipbuilding - Largest supplier of US Navy surface combatants. The share of this segment has been shrinking in the company's product mix. Reduced demand for amphibious assault ships and delays in new contracts have constrained revenue growth. Despite this, it showed steady performance in the past year with six destroyers and amphibious ships under construction.

Mission Technologies (defense solutions, unmanned systems) is the fastest growing segment of the company, increasing by 19% YoY to $2.8 billion as HII focuses more on AI and data analytics solutions. The acquisition of Alion Science and Technology in 2021 marked a major strategic pivot toward high-growth areas like cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and defense solutions. Now, the segment contributes around 25% of total revenues. Mission Tech is expected to grow 1-2% faster than Shipbuilding.

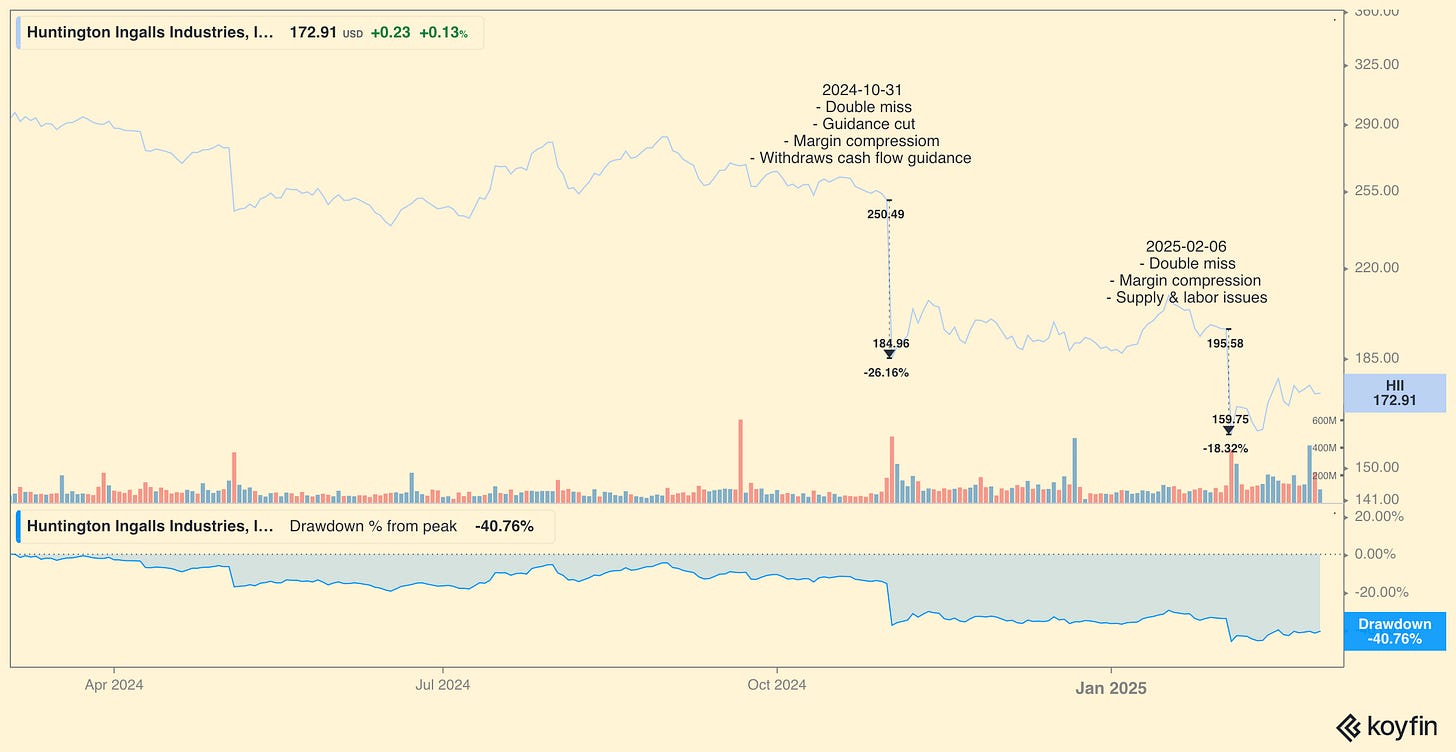

HII's stock price took an 18% hit on February 6 as operating margins contracted from 7.6% to 5% due to fixed-price contracts negotiated before the period of transitory inflation. The Q4 results were even worse - 3.4%, compared to 10.4% in Q4 2023. Moreover, this was the second quarter of missing both the top and bottom lines expectations, and facing significant labor force and supply chain challenges. Altogether, this added up to a 45% drawdown, last experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, management anticipates recovery to 7.5-8% by 2026 through Navy contract renegotiations and workforce expansion initiatives. The Navy has increased budgets to reflect post-pandemic cost realities. HII is renegotiating submarine contracts to include inflation-adjusted pricing, which could lift shipbuilding margins by 2-3%.

Moreover, HII plans a $4.1 billion, 10-year investment in shipyard modernization and automation that aims to reduce labor dependency and improve productivity. Finally, the higher-margin Mission Technologies segment is ramping up and it is expected to grow to 30% of revenue by 2027.

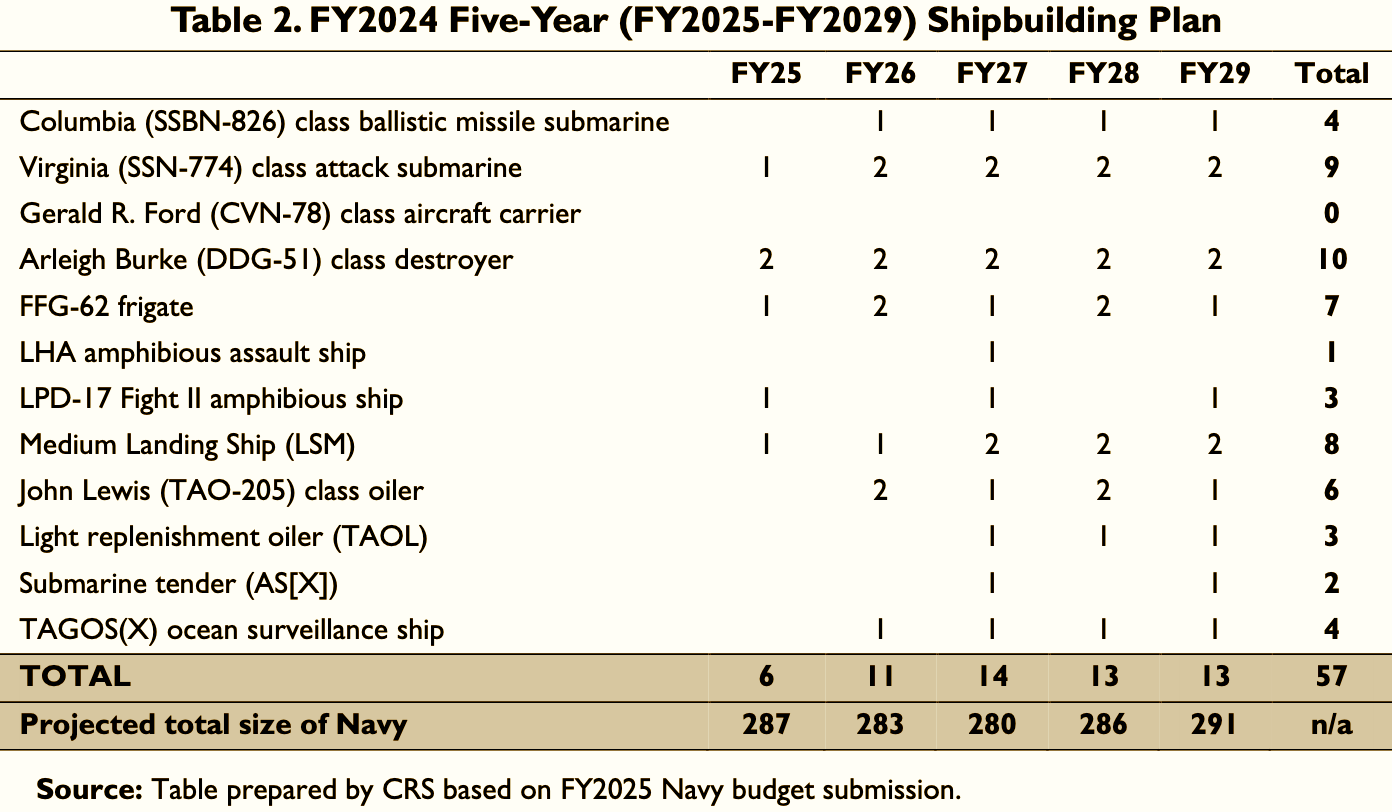

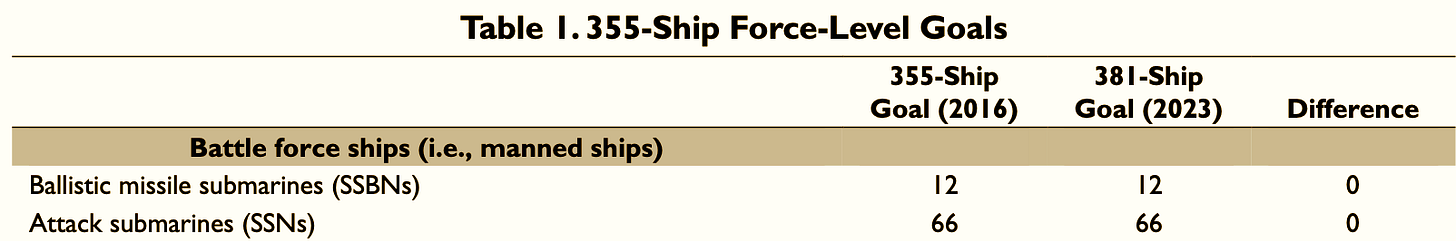

With the U.S. Navy prioritizing a 355-ship fleet (currently ~290), HII’s backlog of 43 vessels ($48 billion) ensures revenue visibility into the 2030s. The Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program, critical for nuclear deterrence, represents $120 billion in long-term contracts.

The Navy Budget

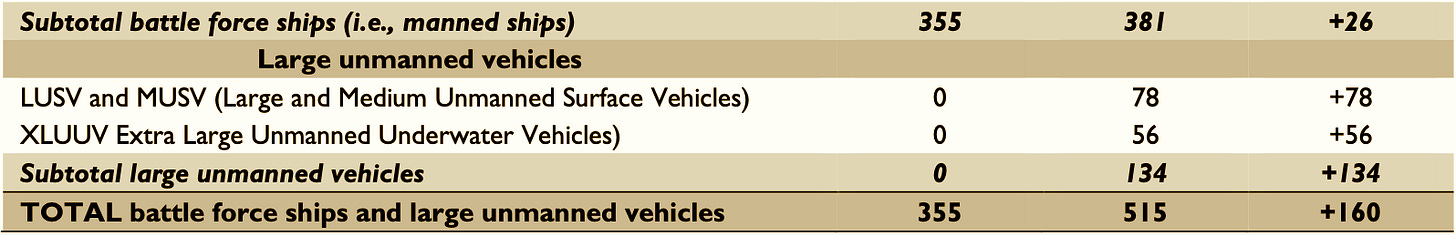

Congressional focus on the Navy's size and composition has been heightened due to the increasing capabilities of the Chinese navy and the capacity of China's shipbuilding industry compared to that of the US.

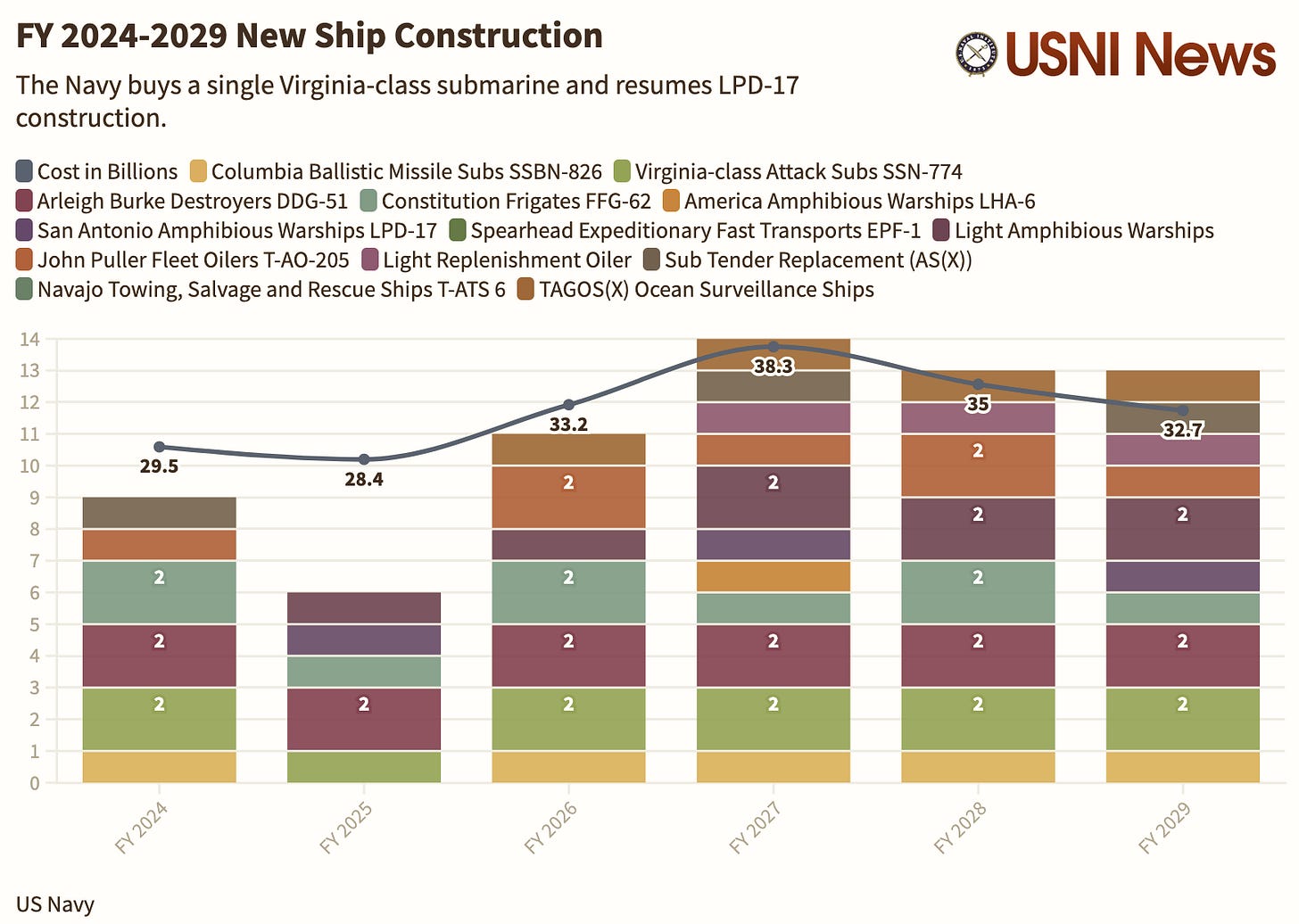

Faced with fiscal constraints, the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2025 budget prioritizes readiness over modernization, leading to a smaller shipbuilding request and a delay for several new programs and research and development efforts.

The request...is seeking one Virginia-class attack submarine, two Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, one Constellation-class frigate, one San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock and one Medium Landing Ship.

While the FY25 budget reflects a commitment to sustaining naval readiness and addressing industrial bottlenecks, it also represents a step back in terms of fleet expansion compared to both prior projections and long-term force structure goals. Achieving a larger fleet will require substantial increases in future budgets beyond current levels, as highlighted by CBO analyses.

The Department of the Navy’s FY25 budget request stands at $257 billion, a 6% increase from FY 2024, reflecting a focus on maintaining naval dominance and aligning with the National Defense Strategy (NDS). Total Navy spending is projected to grow from $255 billion today to $340 billion by 2054, driven by shipbuilding, operations, and maintenance costs.

The Navy plans to retire 19 ships in FY 2025, including 10 ships before the end of their service lives, resulting in a net fleet reduction of nine ships (from 296 to 287). The long-term goal remains achieving a fleet of 355–381 ships, but current funding levels fall short of the annual shipbuilding pace required to meet this target.

Shipbuilding investments total $32.4B (down from $32.8B in FY24), funding six ships. This is down from the seven projected in last year’s five-year plan and below the long-term average of 10–11 ships per year needed to meet fleet expansion goals.

Challenges

The Navy is struggling with labor shortages and massive delays in the submarine (12-16 months) and lead ship program (36 months).

The projected shipbuilding delays announced by the Navy in April 2024, are described as "an unusual and arguably extraordinary situation in the post-WWII history of the Navy."

The most prominent shipbuilding industrial base capacity constraints are those for building submarines. Virginia-class attack submarines have been procured at a rate of two boats per year since FY2011, but the submarine construction industrial base since about 2019 has not been able to complete two Virginia-class boats per year, resulting in a growing backlog of Virginia-class boats that have been procured but not completed. Since 2022, the completion rate has been about 1.2 to 1.4 Virginia-class boats per year. The Navy aims to increase the completion rate two 2.0 Virginia-class boats per year by 2028.

The Navy’s goal for increasing the Virginia-class production rate to 2.0 Virginia-class boats per year by 2028 is part of a larger goal for ramping submarine production up to a rate of one Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine and two Virginia-class submarines per year by 2028.

Options for addressing these constraints include strategic outsourcing, industrial base funding, worker nationwide advertising, and worker immigration, though the latter is hardly an option with the new administration.

The workforce problem brings drones, the topic of my previous post front and center. They are smaller, cheaper to manufacture, and unmanned.

Release the Kraken!

The most amazing thing about the deep sea is that we still know so little about it. We've only explored about 5% of Earth's oceans.

Nuclear Submarines and Drones

SSBNs, such as the U.S. Columbia-class, form the sea-based leg of nuclear triads. This is the three-pronged (land, sea, air) military strategy that ensures a credible second-strike capability, thereby deterring potential aggressors through the concept of mutually assured destruction (MAD). No existing drone sub can replicate this role, as they lack the payload capacity, secure communication links, and reliability required for nuclear deterrence.

Drones, by contrast, are typically mission-specific, with limited modularity for heavy weapons or multi-role operations. Drone subs excel in roles too risky or repetitive for manned submarines:

mine countermeasures

intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR)

decoy operations

There is significant room for synergies between the two types of systems. Forward-deployed SSNs increasingly act as UUV motherships. The US Virginia-class subs now launch/recover drones like Razorback via torpedo tubes. These drones can scout ahead, feeding data to the host submarine. They can engage targets while the host remains undetected. They can clear paths in minefields. And on a darker note, drones can carry out infrastructure sabotage, targeting undersea cables and pipelines.

Forecasts expect 30–50% of undersea operations to involve UUVs by 2040. Currently, UUVs handle niche roles and less than 10% of missions. While nuclear submarines will remain the centerpiece of naval power, UUVs are much better suited for routine (ISR), risky (mine sweeping), and mass-scale missions. The cost advantages are striking. A Virginia-class SSN costs ~$3.4B vs $50M for an Orca XLUUV. Deploying 10 UUVs per SSN could reduce costs by 80% for routine patrols.

China

China's shipbuilding capacity is reportedly 200 times greater than that of the US, according to leaked US Navy intelligence. The US shipbuilding sector employs 150,000 workers, compared to China’s 800,000, with 35% of US naval architects and engineers eligible for retirement by 2030.

If, indeed, the US is losing its naval advantage at this fast a pace, it would make more sense to refocus on the cheaper, nimbler alternative that drones offer to augment the conventional Navy fleet.

As of 2025, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has solidified its position as the world’s largest navy by number of ships, with a battle force exceeding 370 platforms. In contrast, the US Navy’s battle force stands short of 300 ships. This divergence has sparked intense debate about whether the US can reverse its relative decline in naval power, particularly given China’s overwhelming shipbuilding capacity.

China's fleet may be inferior to the US Navy's, but the if they are building more and iterating faster, it is virtually certain that China will catch up in quality and will far surpass the US in quantity. Moreover, the US is actively entrenching itself, which makes it seem extremely unlikely that it will stick its neck out for Taiwan. Even if this is so, it seems unlikely that the US will cut spending on nuclear subs and aircraft carriers - just to maintain its ability to project power and deter adversaries.

In any case, to offset China’s numerical advantage, the US Navy has prioritized:

Unmanned systems: The “Ghost Fleet Overlord” program aims to deploy 150 unmanned surface vessels (USVs) by 2045, providing scalable reconnaissance and strike capabilities while reducing crewed platform risks.

Directed-energy weapons: Laser and railgun systems under development for the DDG(X) next-generation destroyer could neutralize missile swarms and lower per-intercept costs.

Network-centric warfare: The “Project 33” initiative seeks to integrate artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning into maritime operations centers (MOCs), enabling real-time data fusion across carrier strike groups and allied forces.

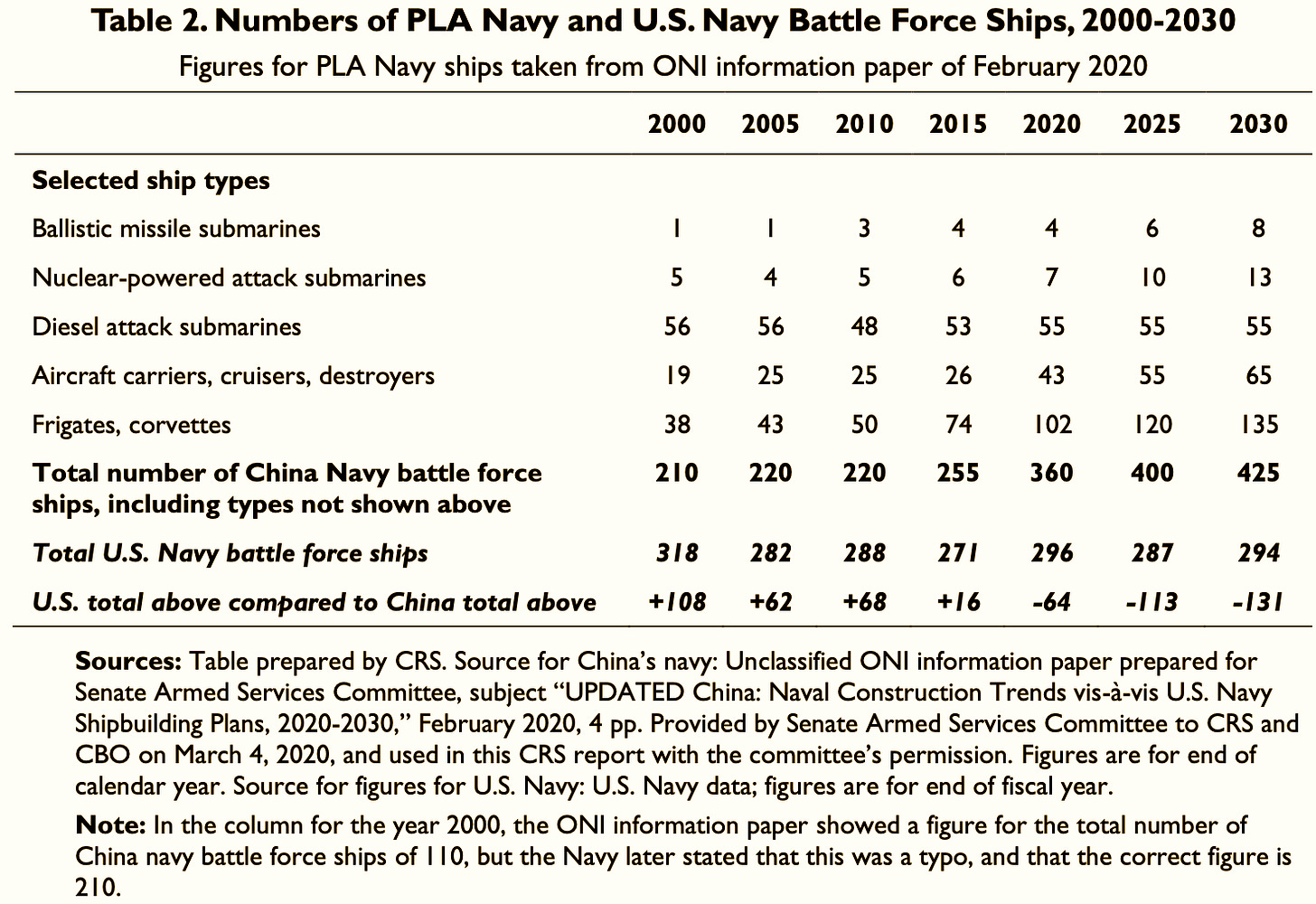

The initiatives are more suited for companies like Kraken and Anduril. Nevertheless, the budgets for production and maintenance of nuclear subs and aircraft carriers are unlikely to go down, even in the conservative scenarios. The Pentagon’s FY26 budget guidance exempts submarine programs from cuts, signaling their centrality to national security. Analysts project substantial growth in US defense spending on nuclear subs and aircraft carriers over the coming decades, driven by strategic priorities to counter near-peer adversaries like China and Russia.

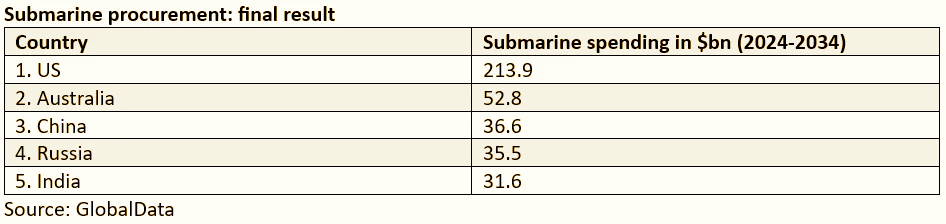

The Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program remains the US Navy’s top acquisition priority, with analysts forecasting $213.9 billion in spending over the next decade for nuclear submarine procurement alone. Analysts emphasize that delays or cost overruns in the Columbia-class program could jeopardize strategic deterrence capabilities, given the Ohio class’s planned retirement starting in 2027.

Alongside SSBNs, the Virginia-class nuclear attack submarine (SSN) program is projected to receive sustained investment. Current plans aim to procure 2–3 Virginia-class SSNs annually through 2043, targeting a fleet of 66 attack submarines to meet growing operational demands in the Indo-Pacific. However, analysts caution that achieving this goal requires annual defense budget growth of 3–5% above inflation—a target challenged by competing priorities and potential fiscal stagnation.

The Gerald R Ford-class (CVN-78) supercarriers represent the cornerstone of US power projection. Analysts forecast $14.0 billion per carrier for the latest CVN-82 variant, reflecting a 9% cost increase over the CVN-81 ($12.9 billion).

The US is still projected to spend more on submarines over the coming decade than all other large spenders.

One has to be conscious, though, that forecasts are inaccurate even during the best of times. In today's environment, they have even less weight.

Financials

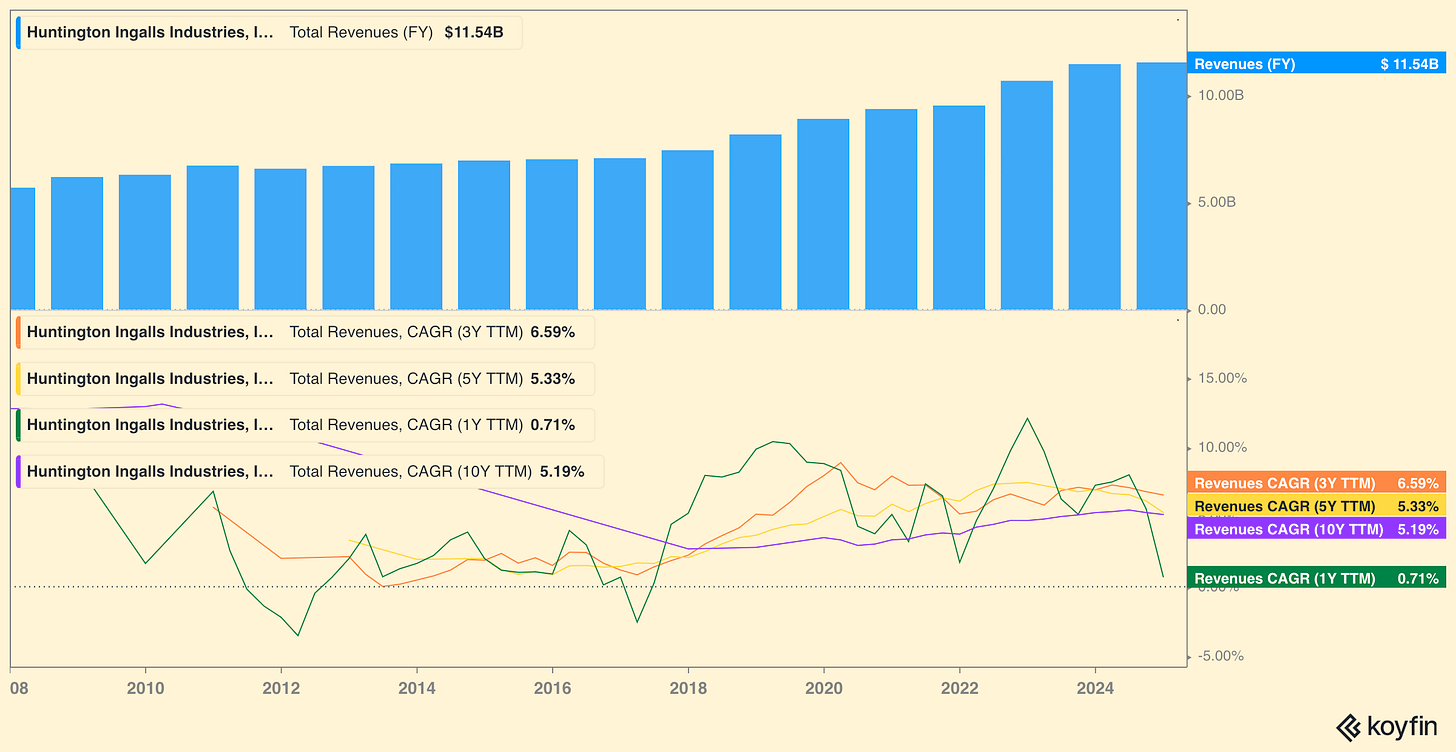

Huntington's revenues are growing steadily at a pace slightly above inflation. As already mentioned, that last part is put under pressure presently. The 10Y CAGR is 5.2%. It used to be more than double this in the not-so-distant past.

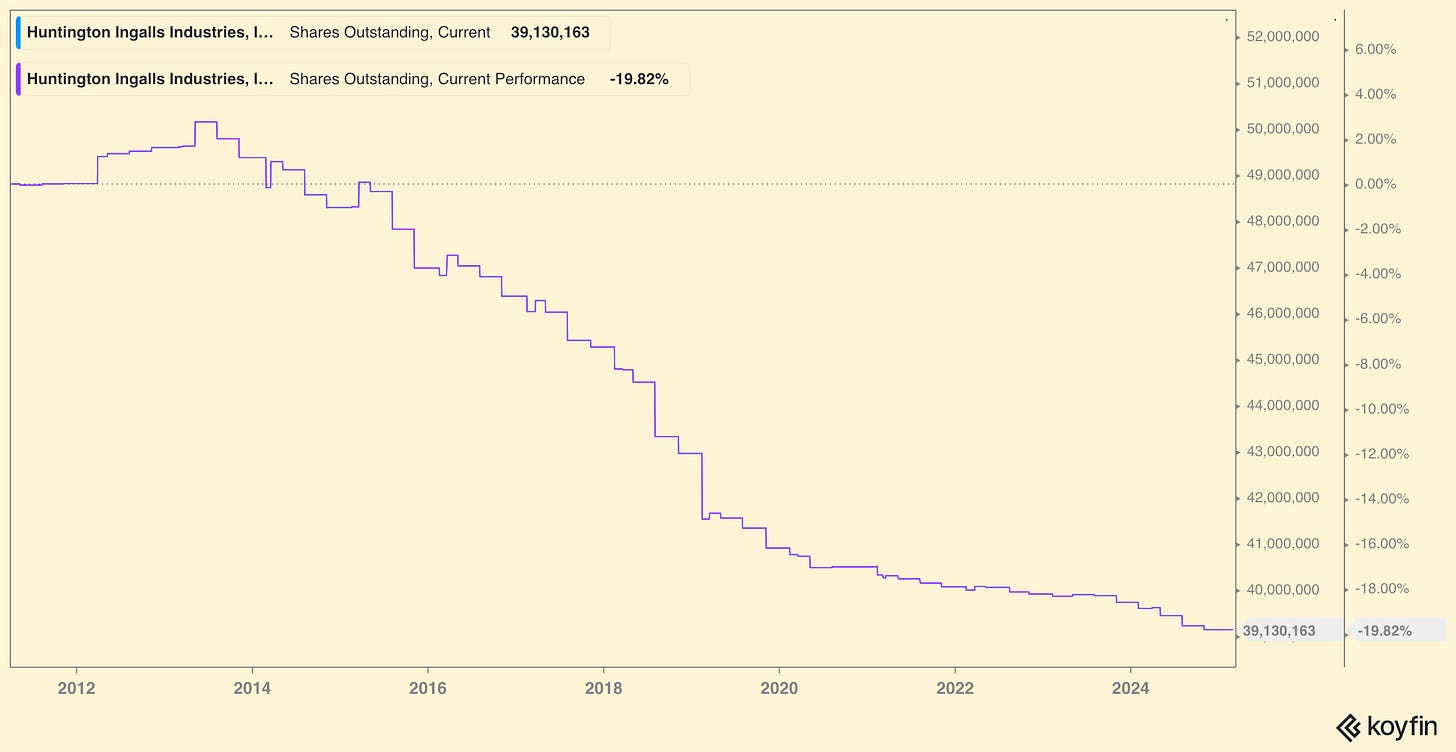

One good thing about HII is that it is a bit of a share cannibal. The company has bought back 20% of its shares in the past 10 years. The rate of buybacks has declined, and for a good reason. Following the Boeing debacle, I expect management to be much more judicious about stock buybacks.

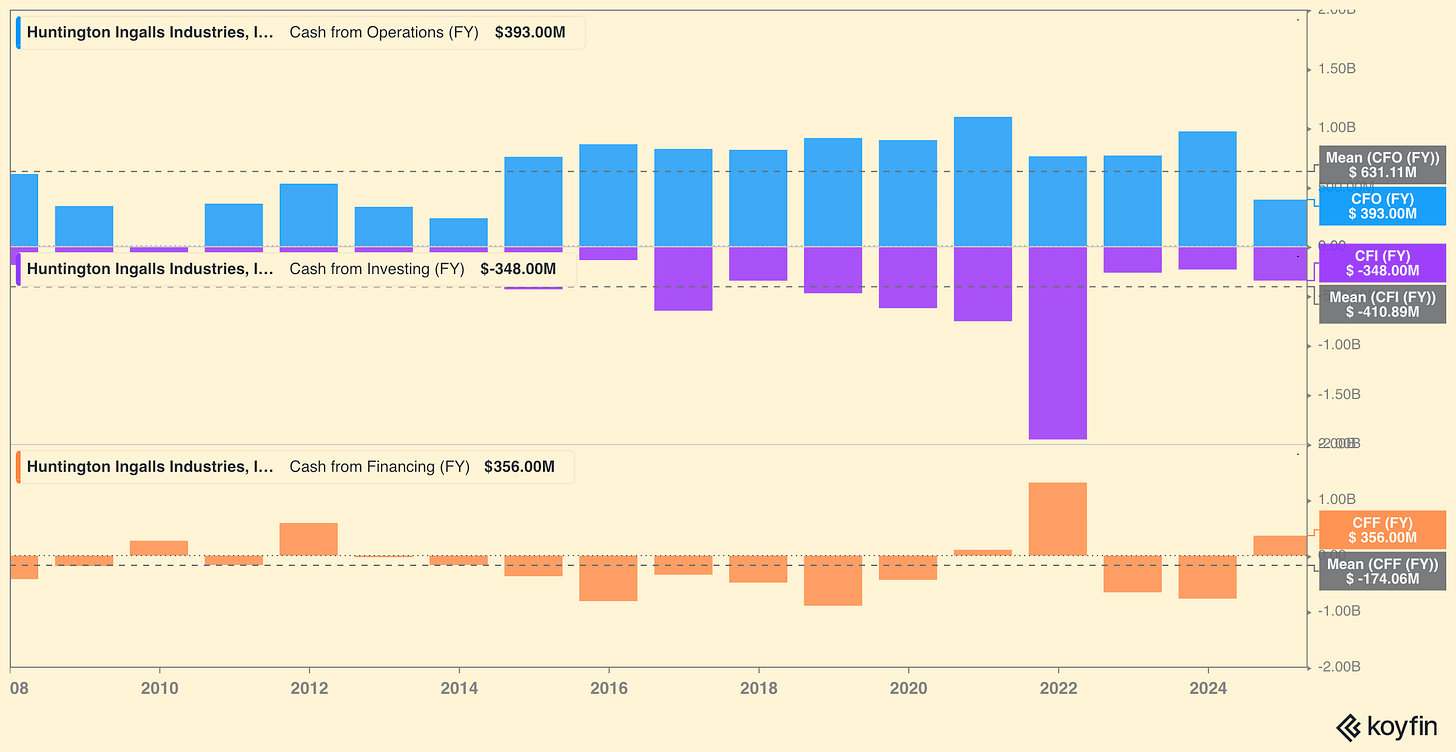

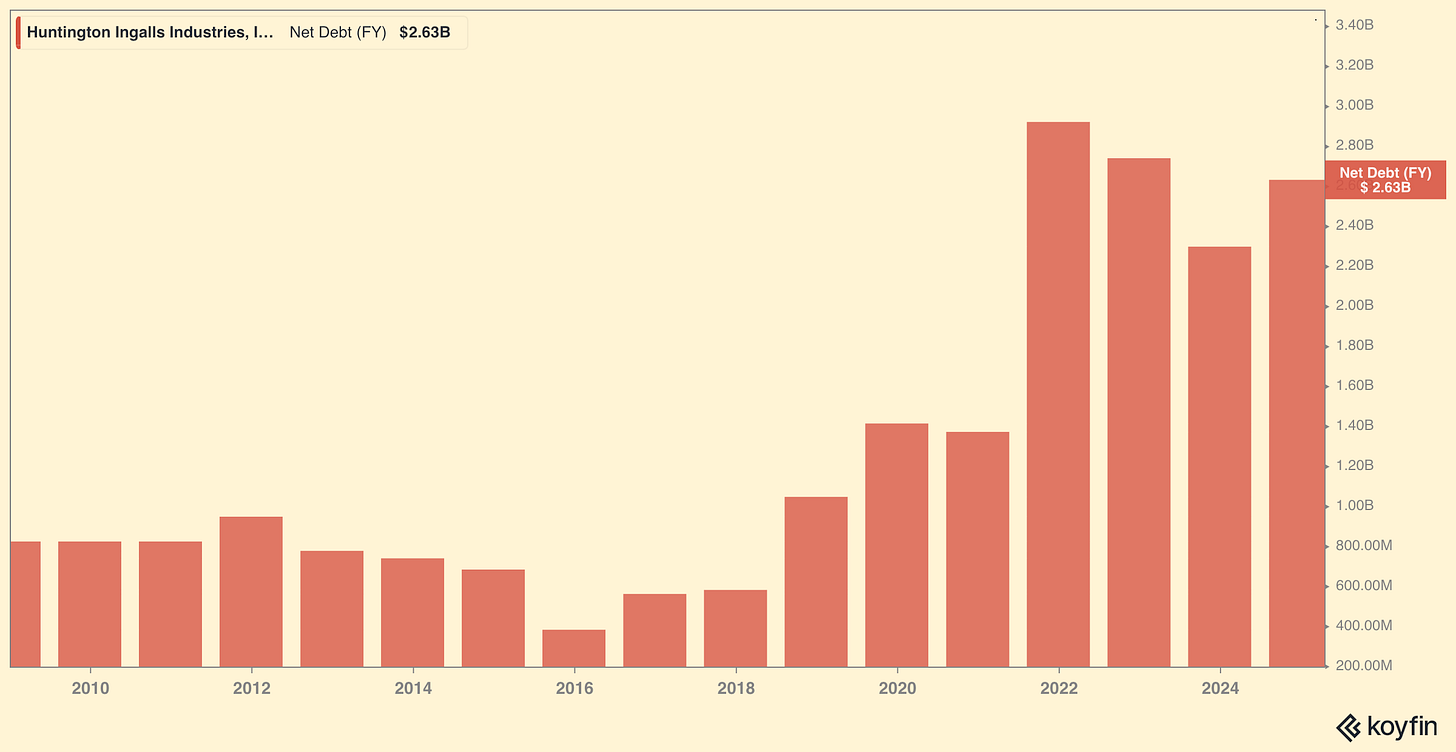

Over the past decade, the company generated around $800-900M cash from operations. It spent roughly half on capex and the other half on repurchases and dividends. This was giving shareholders a nice combined yield of 5-6%, which was great. Until debt ballooned in the 2021 acquisition of Alion (cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and military training and simulation) for $1.65B in cash.

In the past 3 years, HII spent $1.1B repaying debt, and it still has $2.7B left. This is almost double the debt level before the acquisition. Also, rolling the debt over is more expensive today. The interest rate on the 2030 senior notes issued in 2021 was 4.2%. The rate on the same notes issued today is 5.353%.

It is not that the debt level is not sustainable. At 7 times EBIT and 60% of capital, it is totally okay for a primer defense contractor - slightly worse than its closest competitor, General Dynamics, but much better than the other primes. However, $150-$200M spent on debt service significantly reduces the free cash flow available to shareholders. Actually, the 20% single-day price decline was in no small part driven by the company's withdrawal of its 5-year cash flow guidance.

>"The long-term value equation for HII has not changed. There’s unprecedented demand for our products and services," CEO Chris Kastner told investors during an earnings call. "We remain confident in our mid- to long-term guidance of nine to 10 percent shipbuilding margins, and we firmly believe the actions we are taking will enable us to stabilize performance as we continue to work through these shifts."

Moreover, last year saw a massive reduction of cash from operations due to the problems already mentioned - mainly, fixed-price contracts, labor and supply chain challenges, and lower operating margins. As a result, operating income was down to $535M, down from $781 in 2023. A major part of the thesis for HII is margin recovery.

Finally, the company plants to expand capex to 5% in the 2024-2026 period, before moving back to 2-2.5% from 2027 on. Five percent of roughly $12B revenue translates into $600M. Add the $200M of debt service and there is nothing left for shareholders. The upside is contingent, to a large extent, on capex and debt payments coming down significantly following this restructuring effort. Cutting these expenses by half could free up $400M free cash flow to go towards dividends and buybacks. Margin expansion could boost this to $600M. These numbers indicate an FCF multiple of 11-17x on the current stock price.

Valuation

Over the past few years, HII’s margins have been under significant pressure due to various challenges, but the potential for a return to historical margin levels is a key driver of the bull case for HII.

HII’s operating margin fell to 4.6% in 2024, down from 6.8% in 2023 and significantly below historical norms of 9-10% in shipbuilding. These margins are achievable with operational improvements and contract renegotiations.

Assuming 4% annual revenue growth (aligned with Navy procurement plans) and operating margin recovery to 7.5% by 2026, DCF yields a fair value of $287 per share.

On multiple basis, whether you look at P/FCF or EV/EBITDA, HII trades lower compared to its defense peers.

Looking at the various scenarios, the weighted average price is around $250-260.

Unfortunately, between February 6, when I started writing this, and today the stock price already bounced 20%. Not that I am complaining. I have a position, and I may add to it, if the price tumbles again under $170.

Risks

Fixed-price contracts: 60% of HII’s contracts are fixed-price, exposing margins to cost overruns. If they don’t manage to renegotiate with the Navy, their business will not viable given. Nobody wants this, so I wouldn’t put too much weight into it.

Skilled workforce: Shipbuilding requires 40,000+ skilled workers; unemployment in manufacturing remains near record lows (3.8%), driving wage pressures. This one is probably the most pressing concern facing the company today. Skilled workers are scarce and Trump is only going to make them scarcer.

Defense spending de-prioritizes Navy: The logic here is that the US is entrenching. It is protected by two oceans on either side anyway. Why spend on a Navy? It sounds ridiculous, but nothing is off the table anymore.