Deliberate Practice #2: Coca-Cola (KO) in 1988

These are my thoughts on Whopper's Deliberate Practice #2, where we look at Coca-Cola in 1988 - the time when Buffett made his big purchase of over $1 billion. What I found most striking was that all of what Buffett saw, and later talked about, is in plain sight, right in the annual report:

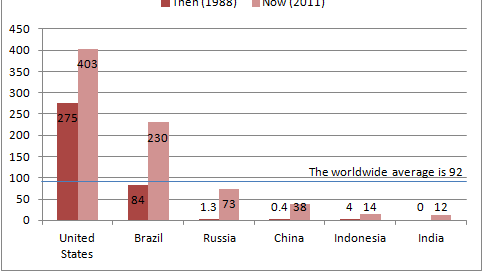

We are the world's only global soft drink company; our internati…